|

InscriptiFact: A Networked Database of Ancient Near Eastern Inscriptions Project Overview

By Bruce Zuckerman, Marilyn Lundberg and Leta Hunt

West Semitic

Research

Project Description InscriptiFact is a data and image base system for optimal use and distribution of image archives of ancient inscriptions and material culture from the Near Eastern and the Mediterranean World. The name "InscriptiFact" is intended to convey the concept of a scholarly archive based on "facts" about "inscriptions" and "artifacts." The initial participants, West Semitic Research (WSR), University of Southern California (USC) West Semitic Research Project and the University of Illinoisí (UI) Ugaritic Texts Digital Edition Project, are acknowledged leaders in the application of photographic techniques to capture and analyze data of ancient texts. Their collective image archives comprise the largest assemblage of image data for these texts in the world. The image archives include the Dead Sea Scrolls, Hebrew, Aramaic, and Canaanite texts from the biblical period and earlier, Mesopotamian documents and medieval Jewish manuscripts as well as numerous other inscriptions and artifacts of archaeological and historical importance. It includes the oldest biblical text currently extant and the oldest complete Hebrew bible in the world. It includes what are possibly the earliest known alphabetic inscriptions. The archive now contains about 100,000 images with more being added every day. The consortium continues to develop and apply the latest photographic and imaging techniques to create the most legible images of these texts found anywhere (Figure 1). Figure 1. Advanced photographic techniques result in substantial information gain.

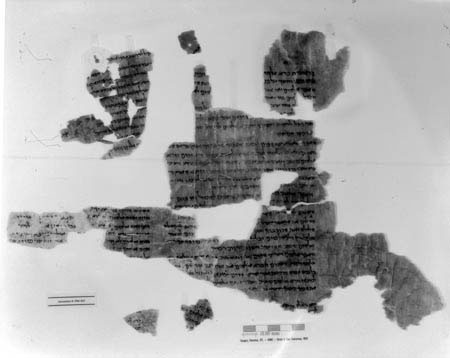

This Dead Sea Scroll (4Q2 Genesis b ) illustrates the significant information gain that can result from research on optimal photographic techniques (in this case, infrared lighting) applied to the study of ancient texts. Members of the proposed InscriptiFact consortium are actively involved in site research in which a wide range of techniques and procedures are used to establish methodologies optimal for a given corpus.

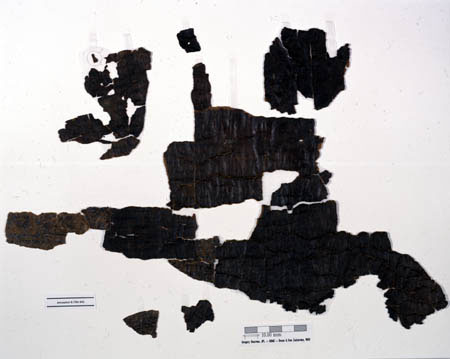

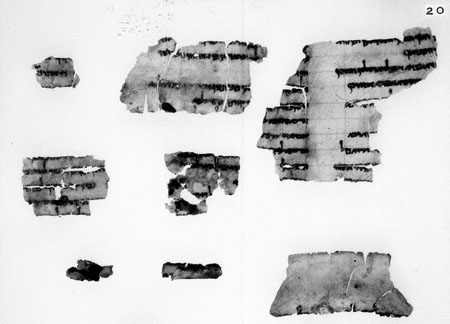

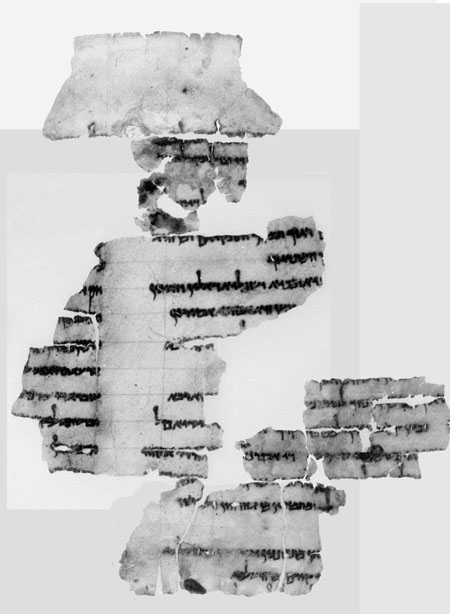

Significant barriers obstruct access to these ancient documents. Original manuscripts are scattered in museums, libraries and archaeological sites. Text fragments, and images of text fragments, are often separated, so that pieces of a single text reside in various, frequently remote, institutions throughout the world, each with its own security protocols and national, cultural and political issues. (See Figure 2.) Even where photographic images are available, they are usually poorly catalogued, in inadequate archival storage and condition and invariably difficult to find.

Figure 2 Ancient texts often exist as a collection of fragments.

Dead Sea Scroll fragments (1Q20 Genesis Apocryphon) illustrate the fragmentation common to ancient texts. Image A shows fragments prior to reassembly and Image B shows one possible reconstruction. The fragments of the full document are found in three different collections in Israel, Jordan and Norway.

An additional barrier to effective access and analysis is the necessity of viewing and comparing images at high resolution. Images of fragments must be viewed side-by-side at maximum detail and at a common scale in order to match or compare them effectively. All potential inscriptional data must be carefully analyzed to distinguish the inscribed material from the noise of deterioration.

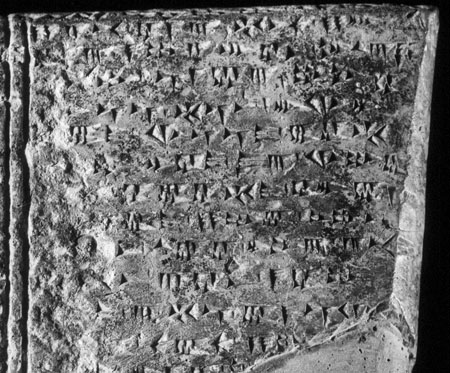

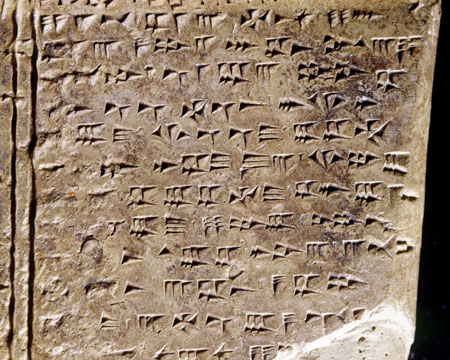

Figure 3 provides an illustration. Image A was captured in the 1930s whereas Image B was captured in the 1990s. A sector-by-sector comparison of the two images at high resolution reveals that inscribed information on the original tablet, as detailed by the 1930s image, is missing in the 1990s image. That is, the tablet itself has deteriorated in the six-decade period between A and B. This might not be noticed at first because B is a technically superior image. The availability of high resolution, precision-matched images dramatically increases a scholar's ability to make subtle comparisons that are crucial for deciphermentócomparisons that would be impossible employing conventional methods. The capacity to bring together, view and compare images of text-fragments located at various institutions at high resolution will, in itself, decisively enhance the ability to reclaim inscriptions and interpret their meaning.

Figure 3. Side-by-side comparison of a section of a Ugaritic tablet.

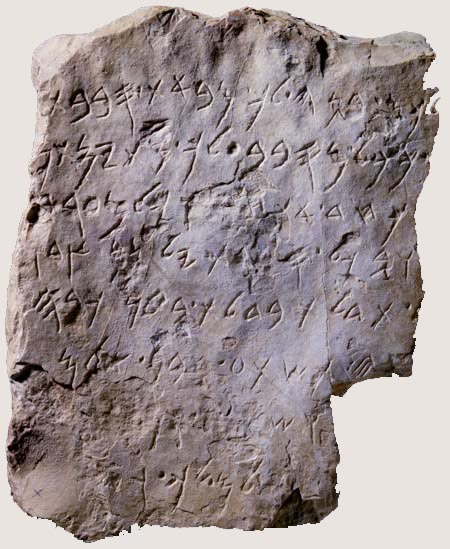

Image A, a section of a Ugaritic Tablet, captured in the 1930s, contains information that no longer exists in B, captured in the 1990s, although B is the superior image (see B' vs. A'). Precise comparisons are necessary on all images for optimal evaluation of the range of information.

The InscriptiFact Internet Database, Part I, facilitates the availability of materials on a global network irrespective of where objects reside. Since text fragments are often stored in scattered locations, search and retrieval of a given text results in presentation of the available fragments in logical order, regardless of the collection or location of individual fragments. In addition, multiple images are usually presented which represent different types of film, different lighting angles, and different levels of magnification.

Broader Impacts of InscriptiFact The InscriptiFact Project will provide an enduring, collaborative information environment. It is expected to result in new technologies for analyzing the documents that serve as the foundation and point of reference for Western culture. It will benefit the intellectual community of linguists, archaeologists, and philologists. It will advance public use in creative ways by providing an educational view of ancient texts and scholarly commentaries. It will facilitate the integration of scientific tools with the acquisition, preservation, analysis and distribution of essential knowledge that stands at the base of western civilization. Most importantly, it will establish a methodology and model for the analysis of ancient inscriptions with broad application. This model will facilitate scientific inquiry and the fullest interchange of information. It will serve as a model for other scholarly projects involving textual data in a wide range of contexts. Conclusion There is an urgency to preserve and analyze imagery of these ancient documents. The physical objects containing the data continue to degrade at an accelerated rate. Images captured only a few decades ago indicate the presence of information no longer evident in imagery of the last decade. Early photographic images are also deteriorating rapidly. A "window of opportunity" currently exists for the InscriptiFact consortium to fulfill a leadership role in establishing a methodology for the physical analysis, preservation and distribution of essential knowledge that underpins and records the civilizations at the foundation of our modern world. --------------------------------------------------------------- Cover Illustration: The Amman Citadel Inscription The modern city of Amman, Jordan, sits on the site of ancient Rabbath-ammon, capital of the ancient territory of Ammon. Ammon was one of ancient Israel's neighbors and, quite often, one of her enemies. In Deuteronomy 23:3-6 Ammonites and Moabites are forbidden to enter the "assembly of the LORD," because they hired Balaam to curse the Israelites as they encamped in the plains of Moab on their way to the land of Canaan. However, the account in Numbers 22-24 does not mention the involvement of the Ammonites. The Inscription pictured here was found in the 1960's in the Citadel, or fortress, of Amman, ancient Rabbath-ammon. It is generally believed to be a building inscription (9th Century BC) of either a temple or the Citadel itself, although some have suggested that it is an oracle or instruction from the god Milkom, god of the Ammonites. The text contains a number of references to parts of buildings, but also has elements of a curse. If it is a building inscription, it fits into a well-known type of text in the ancient Near East. It was customary when building a large public building to attach a record of who built the structure, why it was built, and to whom the building was dedicated. Because this inscription is incomplete, we cannot be sure of its original purpose. |

|

|

|

| Home Page | Information | Documents | Prototype | What's New |

For additional information write to mlundber@usc.edu or lihunt@usc.edu. |